Inside The LC: The Strange but Mostly True Story of Laurel Canyon and the Birth of the Hippie Generation: Part XV

(Part 15 – Post 1 of 3)

PART XV

The Byrds were the very first folk-rock band to take flight, and the one that achieved the greatest fame, but to many discerning ears, Laurel Canyon’s other folk-rock powerhouse, the Buffalo Springfield, was the more talented band.

In the literature chronicling the 1960s music scene, few stories are repeated more frequently than the legend surrounding the formation of what would later be regarded as perhaps the first ‘supergroup.’ All such accounts unquestioningly retell the story as though it were the gospel truth, seemingly oblivious to the improbability of virtually every aspect of the legend. And curiously, virtually every version of the story contains some form of the word “serendipity,” as though everyone has been copying off the same kid’s homework.

As the story goes, Stephen Stills and Richie Furay, formerly of the Au Go-Go Singers, had recently transplanted themselves to Los Angeles after the breakup of the manufactured folkie group. Stills had been the first to relocate, in August of 1965. Furay flew out to join him in February 1966,

after spending a little time working at defense giant Pratt & Whitney, and the two set their sights on putting together a folk-rock band.

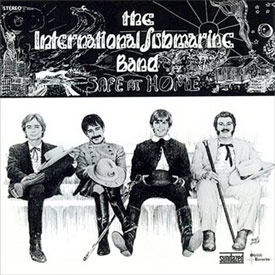

Meanwhile, up in Toronto, Neil Young and Bruce Palmer were playing in a band known as the Mynah Birds –

a band fronted by an AWOL Navy man known as Ricky James Matthews, who would later morph into funkmeister/torturer/rapist Rick James, but whose real name was James Ambrose Johnson, Jr.. The Mynah Birds broke up in March of 1965, just after authorities came calling on Matthews and tossed him in the Brooklyn Brig. Now in search of a new band, Young made the curious decision to head out to LA, for no better reason than that he had what Palmer described as “a hunch, a feeling that … Stephen Stills was in LA.”

Of course, Young had no clue if Stills was in fact there, nor did he know anyone else in LA. And you would think that he would have realized that, even if Stills was there, there was virtually no chance of finding some random person in a city of millions, especially when the person doing the searching had no idea how to get around the city. But no matter. Neil had a calling, so he jumped into an old hearse, of all things, recruited Palmer to ride shotgun, and the two set off on the lengthy trek to Los Angeles.

They arrived, the legend tells us, on April 1, 1966 – April Fool’s Day, appropriately enough – and began the search for Stills. Several days of searching yielded no results, however, and on the afternoon of April 6, the frustrated pair decided to head off to San Francisco in the hopes that maybe they would have better luck finding Stephen there. Perhaps they were going to go on a tour of all the big cities in America, in the hopes that somewhere along the way they might find Stephen Stills.

But as fate would have it, just as they were about to head out of town, Stephen Stills

found them. As Barney Hoskyns tells the story in his

Hotel California, “Early in April 1966, Stills and Richie Furay were stuck in a Sunset Strip traffic jam in Barry Friedman’s Bentley. As they sat in the car, Stephen spotted a 1953 Pontiac hearse with Ontario plates on the other side of the street. ‘I’ll be damned if that ain’t Neil Young,’ Stills said. Friedman executed an illegal U-turn and pulled up behind the hearse. One of rock’s great serendipities had just occurred. Young, a lanky Canadian, had just driven all the way from Detroit in the company of bassist Bruce Palmer. They’d caught the bug that was drawing hundreds of other pop wannabes to the West Coast.”

The pair had actually driven out from Toronto, not Detroit, and the hearse was a 1959 model by most accounts, and Stills and Furay were in a van rather than a Bentley, but such inconsistencies are typical of all Hollywood legends. In any event, John Einarson, in

For What It’s Worth, supplies a somewhat longer, and more hyperbole-filled, version of the legend: “What transpired next is no longer considered simply a chance encounter. Transcending mere fact, the events of the next few minutes have taken on mythic proportions to become, in the annals of popular culture, legendary. More than pure luck, coincidence or serendipity, at that very moment the planets aligned, stars crossed, everyone’s karma turned positive, divine intervention interceded, the hand of fate revealed itself – whatever you subscribe to in order to explain the unexplained. Though each of the five participants in that moment in time tell it slightly differently, the fact remains that the occupants of the white van, individually or collectively, depending on who’s retelling it, noticed the black hearse with the foreign plate heading the other direction. Once the light of recognition came on, the van hastily pulled an illegal, and likely difficult in rush hour, U-turn, maneuvering its way through the line of northbound cars, horn honking frantically all the while, to pull up behind the hearse. One of the passengers leapt out, ran up and pounded on the driver’s side window of the strange vehicle, yelling to the startled travelers inside who had taken no notice of the blaring car horn directly behind them. ‘Hey Neil, it’s me, Steve Stills! Pull over, man!’ The drivers of the two vehicles managed to find curb space or a vacant store parking lot, again depending on whose version is being related, and the five piled out to embrace and introduce one another … On April 6, 1966, in that late afternoon line of traffic, the course of popular music was altered forever.”

Anyone who actually lives and drives in LA likely knows that “difficult” is not really the word to describe the feasibility of making an impromptu U-turn in rush hour traffic on the Sunset Strip; the correct word would be “impossible,” which is the same word that accurately describes the likelihood of that van “maneuvering its way through the line of northbound cars,” or of it finding “curb space” on Sunset Boulevard. But let’s just play along and assume that Neil Young and Stephen Stills, each of whom, for some reason, had been dreaming about forming a band with the other, had a random, chance encounter on Sunset Boulevard. In that brief moment in time, a band was formed – or at least 4/5 of a band.

Retiring to the home of Barry Friedman, who would later legally change his name to Frazier Mohawk, the quartet of musicians quickly decided that their newly-formed band would only perform original material. With no less than three singer/songwriter/guitarists on board (Furay, Young and Stills), along with a bass player (Bruce Palmer), all that was needed was a drummer. Three days later, on April 9, 1966, they acquired one, in the form of Dewey Martin, formerly with the Dillards.

The Dillards, as it turns out, had just decided to go back to their acoustic bluegrass roots, so they no longer needed a drummer. They also apparently had no further need for a whole bunch of new electric instruments and stacks of amplifiers, so Dewey, according to legend, brought all of that with him. Because the Dillards, you know, were just going to throw it all away anyway. So now, with the stars all properly aligned, the band was not only complete but they each had shiny new electric instruments to play – and it all had magically come together in just 72 hours.

There was still much work to be done, of course. For one thing, they all had to learn to play those shiny new electric instruments.

And they all had to learn to play together as a band. And they had to build up a repertoire of original songs. And they had to rehearse and polish those songs. But not to worry; they had, as we’ll see, at least a couple of hours to work on each of those things.

Unlike, say, the Byrds, the members of the Buffalo Springfield were, by all accounts, talented musicians from the outset. Stills and Young were both skilled lead guitarists and songwriters, though Young’s vocals were, to be sure, an acquired taste. Furay was an accomplished rhythm guitarist and songwriter, as well as being the group’s best lead vocalist. Bruce Palmer was a respected bass player who, shockingly, actually had experience playing the instrument. And Dewey Martin, several years older than the rest of the crew, had drummed for such rock and country legends as the Everly Brothers, Charlie Rich, Roy Orbison, Patsy Cline, and Carl Perkins.

None of that, however, explains the absurdly meteoric rise of the Buffalo Springfield. On April 11, 1966, just five days after the quartet had purportedly first met, and

just two days after they had added a drummer and instruments, the band played its first club date at one of Hollywood’s most prestigious venues: the Troubadour. Four days later, on April 15, they played the first of six dates around the southland opening for the hottest band on the Strip: the Byrds. That mini-tour was followed almost immediately by a six-week stand at the hottest club on the Strip, the Whisky. That gig wrapped up on June 20, 1966.

A month later, on July 25, the band landed the opening slot on the most anticipated concert of the year – the Rolling Stones show at the Hollywood Bowl, sponsored by local radio station KHJ.

The station, by the way, had just been launched the previous year, in May of 1965, just a few weeks after the Byrds had taken the world by storm with the release of

Mr. Tambourine Man and sparked a folk-rock revolution. Just as new clubs had magically appeared along the Sunset Strip in anticipation of the about-to-explode music scene, so too did a radio station magically appear to promote those new clubs and the artists filling them. Such things tend to happen, as we know, rather, uhmm, serendipitously.

Another guest at the hotel at that same time, incidentally, was Rod Stewart (at whose home, readers of Programmed to Kill will recall, one of the victims of the so-called Sunset Strip Killers would later be last seen).

Another guest at the hotel at that same time, incidentally, was Rod Stewart (at whose home, readers of Programmed to Kill will recall, one of the victims of the so-called Sunset Strip Killers would later be last seen).

That decision is almost universally cast as an innocent mistake on the part of the band, though such a claim is difficult to believe. It was certainly no secret that the reactionary motorcycle clubs,

That decision is almost universally cast as an innocent mistake on the part of the band, though such a claim is difficult to believe. It was certainly no secret that the reactionary motorcycle clubs,

The song they were playing, contrary to most accounts of the incident, was Sympathy for the Devil, as was initially reported in Rolling Stone magazine based on the accounts of several reporters on the scene and a review of the unedited film stock.

The song they were playing, contrary to most accounts of the incident, was Sympathy for the Devil, as was initially reported in Rolling Stone magazine based on the accounts of several reporters on the scene and a review of the unedited film stock.

), Vince would later become a golf partner of uber-conservative Senator Barry Goldwater.

), Vince would later become a golf partner of uber-conservative Senator Barry Goldwater.

]

]