You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Tsunami Undersea volcano erupts near Tonga, causing small tsunami waves - NOAA

- Thread starter danielboon

- Start date

packyderms_wife

Neither here nor there.

IIRC this is not the first time this has happened with this particular volcano/island.

packyderms_wife

Neither here nor there.

RT 15:37

Communications down and toxic air after Tonga volcano erupts | 9 News Australia

There are reports Tonga is struggling with toxic air and contaminated water, after an underwater volcanic eruption triggered a tsunami, wiping out communications.

0:00 Communications down and toxic air after Tonga volcano erupts

7:02 Footage shows extent of tsunami damage

7:18 Australia’s Tongan communities wait for news 10:42 Huge tidal surges in Fiji

13:07 Volcanic eruption explained

14:53 Tsunami warning remains for NSW coast

packyderms_wife

Neither here nor there.

Hearing a lot of VEI 5 estimates being used. That may end up being conservative.

This is what I'm hearing as well, VEI 5.

Question in the little research I've done it seems like this massive eruption totally caught scientists off guard. What changed? And will another larger eruption occur?

Volcanic Eruption May Be Biggest Ever Seen From Space

Jan 15, 2022

RT 8:13

View: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zoMRwyNhqJ4&ab_channel=ScottManley

Jan 15, 2022

RT 8:13

Scott Manley

1.38M subscribers

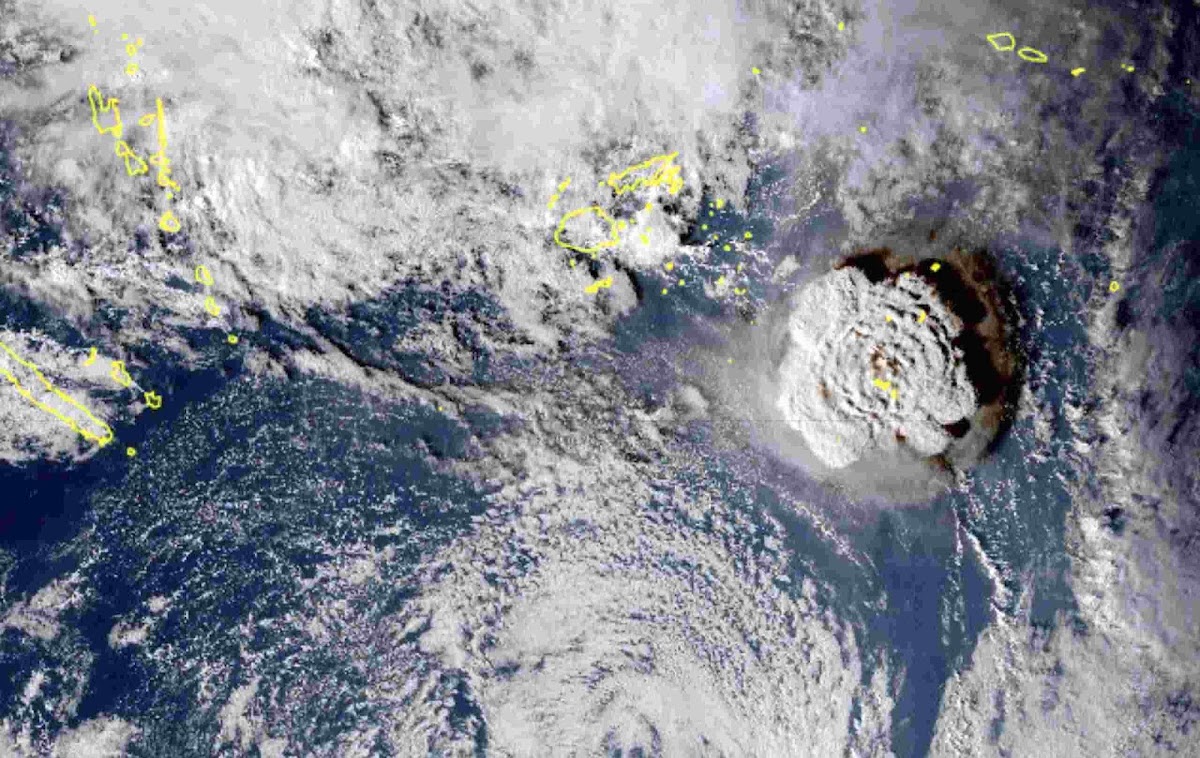

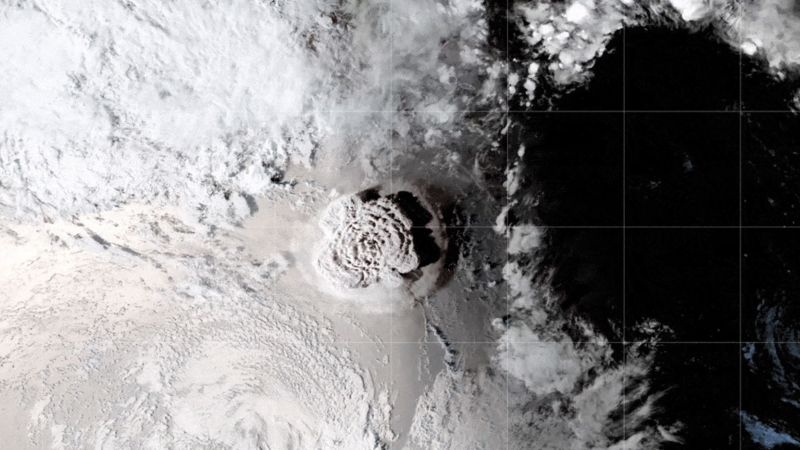

In the last 24 hours we've seen a huge explosive volcanic eruption from the Tongan island of Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai - the blast is so large it's easily visible from multiple satellites in geostationary orbit, tens of thousands of miles up. The blast sent a soundwave around the world which is still being measured and the resulting tsunami caused flooding around the pacific ocean.

Follow me on Twitter for more updates:

I have a discord server where I regularly turn up:

Join the Scott Manley Community Discord Server!

Check out the Scott Manley Community community on Discord - hang out with 7815 other members and enjoy free voice and text chat.discord.gg

If you really like what I do you can support me directly through Patreon

jward

passin' thru

Andrew Greene

@AndrewBGreene

21m

First Australian Defence Force surveillance images of devastation in Tonga

@AndrewBGreene

21m

First Australian Defence Force surveillance images of devastation in Tonga

Masterphreak

Senior Member

Why the volcanic eruption in Tonga was so violent, and what to expect next

The Kingdom of Tonga doesn’t often attract global attention, but a violent eruption of an underwater volcano on January 15 has spread shock waves, qui

Why the volcanic eruption in Tonga was so violent, and what to expect next

on Sunday, January 16, 2022 in Other Science, Planet and Environment

The Kingdom of Tonga doesn’t often attract global attention, but a violent eruption of an underwater volcano on January 15 has spread shock waves, quite literally, around half the world.

The volcano is usually not much to look at. It consists of two small uninhabited islands, Hunga-Ha’apai and Hunga-Tonga, poking about 100m above sea level 65km north of Tonga’s capital Nuku‘alofa. But hiding below the waves is a massive volcano, around 1800m high and 20km wide.

The Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha'apai volcano has erupted regularly over the past few decades. During events in 2009 and 2014/15 hot jets of magma and steam exploded through the waves. But these eruptions were small, dwarfed in scale by the January 2022 events.

Our research into these earlier eruptions suggests this is one of the massive explosions the volcano is capable of producing roughly every thousand years.

Why are the volcano’s eruptions so highly explosive, given that sea water should cool the magma down?

If magma rises into sea water slowly, even at temperatures of about 1200℃, a thin film of steam forms between the magma and water. This provides a layer of insulation to allow the outer surface of the magma to cool.

But this process doesn’t work when magma is blasted out of the ground full of volcanic gas. When magma enters the water rapidly, any steam layers are quickly disrupted, bringing hot magma in direct contact with cold water.

Volcano researchers call this “fuel-coolant interaction” and it is akin to weapons-grade chemical explosions. Extremely violent blasts tear the magma apart. A chain reaction begins, with new magma fragments exposing fresh hot interior surfaces to water, and the explosions repeat, ultimately jetting out volcanic particles and causing blasts with supersonic speeds.

Two scales of Hunga eruptions

The 2014/15 eruption created a volcanic cone, joining the two old Hunga islands to create a combined island about 5km long. We visited in 2016, and discovered these historical eruptions were merely curtain raisers to the main event.

Mapping the sea floor, we discovered a hidden “caldera” 150m below the waves.

The caldera is a crater-like depression around 5km across. Small eruptions (such as in 2009 and 2014/15) occur mainly at the edge of the caldera, but very big ones come from the caldera itself. These big eruptions are so large the top of the erupting magma collapses inward, deepening the caldera.

Looking at the chemistry of past eruptions, we now think the small eruptions represent the magma system slowly recharging itself to prepare for a big event.

We found evidence of two huge past eruptions from the Hunga caldera in deposits on the old islands. We matched these chemically to volcanic ash deposits on the largest inhabited island of Tongatapu, 65km away, and then used radiocarbon dates to show that big caldera eruptions occur about ever 1000 years, with the last one at AD1100.

With this knowledge, the eruption on January 15 seems to be right on schedule for a “big one”.

What we can expect to happen now

We’re still in the middle of this major eruptive sequence and many aspects remain unclear, partly because the island is currently obscured by ash clouds.

The two earlier eruptions on December 20 2021 and January 13 2022 were of moderate size. They produced clouds of up to 17km elevation and added new land to the 2014/15 combined island.

The latest eruption has stepped up the scale in terms of violence. The ash plume is already about 20km high. Most remarkably, it spread out almost concentrically over a distance of about 130km from the volcano, creating a plume with a 260km diameter, before it was distorted by the wind.

This demonstrates a huge explosive power – one that cannot be explained by magma-water interaction alone. It shows instead that large amounts of fresh, gas-charged magma have erupted from the caldera.

The eruption also produced a tsunami throughout Tonga and neighbouring Fiji and Samoa. Shock waves traversed many thousands of kilometres, were seen from space, and recorded in New Zealand some 2000km away. Soon after the eruption started, the sky was blocked out on Tongatapu, with ash beginning to fall.

All these signs suggest the large Hunga caldera has awoken. Tsunami are generated by coupled atmospheric and ocean shock waves during an explosions, but they are also readily caused by submarine landslides and caldera collapses.

It remains unclear if this is the climax of the eruption. It represents a major magma pressure release, which may settle the system.

A warning, however, lies in geological deposits from the volcano’s previous eruptions. These complex sequences show each of the 1000-year major caldera eruption episodes involved many separate explosion events.

Hence we could be in for several weeks or even years of major volcanic unrest from the Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha'apai volcano. For the sake of the people of Tonga I hope not.

jward

passin' thru

NASA scientists estimate Tonga blast at 10 megatons

January 18, 2022 2:27 PM ET

Geoff Brumfiel

The island of Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai as imaged by the satellite company Maxar on Jan. 6 (left) and Jan. 18 (right). It was obliterated in a volcanic eruption that scientists estimate was 10 megatons in size.

Maxar Technologies

NASA researchers have an estimate of the power of a massive volcanic eruption that took place on Saturday near the island nation of Tonga.

"We come up with a number that's around 10 megatons of TNT equivalent," James Garvin, the chief scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, told NPR.

That means the explosive force was more than 500 times as powerful as the nuclear bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, at the end of World War II.

The blast was heard as far away as Alaska and was probably one of the loudest events to occur on Earth in over a century, according to Michael Poland, a geophysicist with the U.S. Geological Survey.

"This might be the loudest eruption since [the eruption of the Indonesian volcano] Krakatau in 1883," Poland says. That massive 19th-century eruption killed thousands and released so much ash that it cast much of the region into darkness.

In the case of this latest event, Garvin says that he believes the worst may be over — at least for now.

"If the past precedent for volcanic eruptions in this kind of setting has any meaning at all," he added, "then we won't have another one of these explosions for a while."

Even three days after the blast, Tonga remains largely cut off from the world. Undersea communications cables appear to have been cut, and the airport is covered in ash, preventing relief flights from arriving at the capital city of Nuku'alofa.

Reconnaissance flights by the government of New Zealand showed ash had blanketed houses and many other structures. New Zealand's Foreign Ministry reported that two people had been confirmed killed and that a tsunami had inundated the western coast of the main island of Tongatapu, causing major damage. Wire reports cite the government of Tonga claiming one additional death and even more damage on outlying islands, including Mango island, where all homes have been destroyed.

An aerial view of heavy ash fall on Jan. 17 on the island of Nomuka, Tonga. The extent of the damage to the island nation remains largely unknown.

New Zealand Defence Force/Getty Images

The volcano behind the eruption had been the subject of study by the NASA team in the years running up to this explosive event. The islands that form Tonga lie along a subduction zone where one part of the Earth's crust dips under another, according to Garvin.

"In this particular case, we don't know when, a kind of volcano with a big summit ring of hills and things formed," Garvin says.

In late 2014 and early 2015, along the rim of that caldera, volcanic activity built a platform that rose up out of the sea, creating a new island. Layers of steam and ash eventually connected the island, known as Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai, to two much older islands on either side of it.

Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai was completely destroyed by Saturday's explosion, says Dan Slayback, a research scientist for NASA's Goddard, as well as Science Systems and Applications Inc. Slayback says the blast was so massive it even appears to have taken chunks out of the older islands nearby.

"They weren't ash — they were solid rock, blown to bits," he says. "It was quite amazing to see that happen."

Garvin says the island's formation also probably seeded its destruction. As it rose from the sea, layers of liquid magma filled a network of chambers beneath it. He suspects the explosion was triggered by a sudden change in the subterranean plumbing, which caused seawater to flood in.

"When you put a ton of seawater into a cubic kilometer of liquid rock, things are going to get bad fast," he says.

But for all its explosive force, the eruption itself was actually relatively small, according to Poland, of the U.S. Geological Survey. Unlike the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo, which spewed ash and smoke for hours, the events at Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai lasted less than 60 minutes. He does not expect that the eruption will cause any short-term changes to Earth's climate, the way other large eruptions have in the past.

In fact, Poland says, the real mystery is how such a relatively small eruption could create such a big bang and tsunami.

"It had an outsized impact, well beyond the area that you would have expected if this had been completely above water," he says. "That's the thing that's just a head-scratcher."

Garvin says that scientists want to follow up with additional surveys of the area around the volcano's caldera. Satellite imagery analysis is already underway and may soon be followed with missions by drones. He hopes the volcano will be safe enough for researchers to visit later in the year.

Poland says he believes researchers will learn a lot more in the days and months to come, as they conduct new surveys of the area.

"This is just a horrible event for the Tongans," he says. But "it could be a benchmark, watershed kind of event in volcanology."

www.npr.org

www.npr.org

January 18, 2022 2:27 PM ET

Geoff Brumfiel

The island of Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai as imaged by the satellite company Maxar on Jan. 6 (left) and Jan. 18 (right). It was obliterated in a volcanic eruption that scientists estimate was 10 megatons in size.

Maxar Technologies

NASA researchers have an estimate of the power of a massive volcanic eruption that took place on Saturday near the island nation of Tonga.

"We come up with a number that's around 10 megatons of TNT equivalent," James Garvin, the chief scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, told NPR.

That means the explosive force was more than 500 times as powerful as the nuclear bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, at the end of World War II.

The blast was heard as far away as Alaska and was probably one of the loudest events to occur on Earth in over a century, according to Michael Poland, a geophysicist with the U.S. Geological Survey.

"This might be the loudest eruption since [the eruption of the Indonesian volcano] Krakatau in 1883," Poland says. That massive 19th-century eruption killed thousands and released so much ash that it cast much of the region into darkness.

In the case of this latest event, Garvin says that he believes the worst may be over — at least for now.

"If the past precedent for volcanic eruptions in this kind of setting has any meaning at all," he added, "then we won't have another one of these explosions for a while."

Even three days after the blast, Tonga remains largely cut off from the world. Undersea communications cables appear to have been cut, and the airport is covered in ash, preventing relief flights from arriving at the capital city of Nuku'alofa.

Reconnaissance flights by the government of New Zealand showed ash had blanketed houses and many other structures. New Zealand's Foreign Ministry reported that two people had been confirmed killed and that a tsunami had inundated the western coast of the main island of Tongatapu, causing major damage. Wire reports cite the government of Tonga claiming one additional death and even more damage on outlying islands, including Mango island, where all homes have been destroyed.

An aerial view of heavy ash fall on Jan. 17 on the island of Nomuka, Tonga. The extent of the damage to the island nation remains largely unknown.

New Zealand Defence Force/Getty Images

The volcano behind the eruption had been the subject of study by the NASA team in the years running up to this explosive event. The islands that form Tonga lie along a subduction zone where one part of the Earth's crust dips under another, according to Garvin.

"In this particular case, we don't know when, a kind of volcano with a big summit ring of hills and things formed," Garvin says.

In late 2014 and early 2015, along the rim of that caldera, volcanic activity built a platform that rose up out of the sea, creating a new island. Layers of steam and ash eventually connected the island, known as Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai, to two much older islands on either side of it.

Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai was completely destroyed by Saturday's explosion, says Dan Slayback, a research scientist for NASA's Goddard, as well as Science Systems and Applications Inc. Slayback says the blast was so massive it even appears to have taken chunks out of the older islands nearby.

"They weren't ash — they were solid rock, blown to bits," he says. "It was quite amazing to see that happen."

Garvin says the island's formation also probably seeded its destruction. As it rose from the sea, layers of liquid magma filled a network of chambers beneath it. He suspects the explosion was triggered by a sudden change in the subterranean plumbing, which caused seawater to flood in.

"When you put a ton of seawater into a cubic kilometer of liquid rock, things are going to get bad fast," he says.

#NASAWorldview Image of the Week: Explosive Eruption of #HungaTonga - Hunga Ha'apai Volcano as observed on Jan. 15, 2022 by the ABI instrument aboard the @NOAA GOES-West satellite. Learn more: Explosive Eruption of Hunga Tonga - Hunga Ha'apai Volcano | Earthdata GeoColor Imagery provided by NOAA/NESDIS/STAR pic.twitter.com/yRkR0bfg9U

— NASAEarthdata (@NASAEarthData) January 18, 2022

But for all its explosive force, the eruption itself was actually relatively small, according to Poland, of the U.S. Geological Survey. Unlike the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo, which spewed ash and smoke for hours, the events at Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai lasted less than 60 minutes. He does not expect that the eruption will cause any short-term changes to Earth's climate, the way other large eruptions have in the past.

In fact, Poland says, the real mystery is how such a relatively small eruption could create such a big bang and tsunami.

"It had an outsized impact, well beyond the area that you would have expected if this had been completely above water," he says. "That's the thing that's just a head-scratcher."

Garvin says that scientists want to follow up with additional surveys of the area around the volcano's caldera. Satellite imagery analysis is already underway and may soon be followed with missions by drones. He hopes the volcano will be safe enough for researchers to visit later in the year.

Poland says he believes researchers will learn a lot more in the days and months to come, as they conduct new surveys of the area.

"This is just a horrible event for the Tongans," he says. But "it could be a benchmark, watershed kind of event in volcanology."

NASA scientists estimate Tonga blast at 10 megatons

Researchers who have been studying the volcano since 2015 say it was likely caused by seawater flowing into a chamber filled with magma.

jward

passin' thru

AFP News Agency

@AFP

1h

#BREAKING Tonga undersea cable needs 'at least' four weeks to repair: New Zealand

@AFP

1h

#BREAKING Tonga undersea cable needs 'at least' four weeks to repair: New Zealand

Masterphreak

Senior Member

VOLCANIC GRAVITY WAVES OVER HAWAII: The eruption of an undersea volcano near Tonga on Jan. 15th was even bigger than anyone thought. It nearly touched the edge of space. Hours after a mushroom cloud burst out of the Pacific Ocean, cameras at the Gemini Observatory on Mauna Kea recorded red waves rippling over Hawaii:

These are gravity waves, a type of atmospheric disturbance excited by intense thunderstorms and volcanic eruptions. Many gravity waves scud through the low atmosphere. The ripples caught by Gemini's Cloudcam, however, are in the mesosphere 85 km high--the realm of meteors, sprites, and noctilucent clouds.

Photographer Steve Cullen spotted the waves in online footage. "I had a hunch that Gemini Cloudcams might detect gravity waves produced by the eruption of Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai. So, I just took a look and there they were!"

"The volcanic eruption happened at 04:15 UTC, and the gravity waves passed Hawaii 4.5 hours later," notes Cullen. "This corresponds to a speed of ~1100 kilometers per hour"--a good match to the speed of sound in the mesosphere.

The waves are red because of airglow, an aurora-like phenomenon caused by chemical reactions in the upper atmosphere. Airglow is usually too faint to see, but gravity waves from the volcano boosted the reaction rates. Red is a sign of OH. This neutral molecule (not to be confused with the OH- ion found in aqueous solutions) exists in a thin layer 85 km high and can produce a pure red light.

jward

passin' thru

Volcanic Eruption Devastates Tonga

By Joshua Mcdonald for The Diplomat

5-6 minutes

Oceania | Society | Oceania

Tonga is made up of 169 islands, 36 of which are inhabited. It’s expected to take weeks to survey the scale of the damage.

In this photo provided by the New Zealand Defense Force, volcanic ash covers roof tops and vegetation in an area of Tonga, Monday, January 17, 2022.

Credit: CPL Vanessa Parker/NZDF via AP)

The government of Tonga issued its first statement since a violent volcanic eruption occurred Saturday that caused tsunami waves to wreak havoc across the country, leaving at least three people dead, towns destroyed, and the country without internet for several days.

“As a result of the eruption, a volcanic mushroom plume was released reaching the stratosphere and extending radially covering all Tonga Islands, generating tsunami waves rising up to 15 metres, hitting the west coasts of Tongatapu Islands, ‘Eva, and Ha’apai Islands,” the government said.

“To date, there are 3 confirmed fatalities including a British national; a 65-year-old female from Mango Island; and a 49-year-old male from Nomuka Island. There are also a number of injuries reported.”

The government said not a single house is left standing on Mango Island, only two houses remain on Fonoifua Island, and extensive damage has been caused to other islands. It added that evacuation efforts are underway across the country.

The volcanic ash that blanketed Tonga has severely affected water supplies and made any effort by Tonga’s neighbors to fly in support extremely dangerous.

“Challenges to sea and air transportation remain due to damage sustained by the wharves and the ash that is covering the runways,” the government said. “Domestic and international flights have been deferred until further notice as the airports undergo clean-up.”

The government added that communication is still a key issue, with internet still down while domestic phone calls can only operate within the areas of Tongatapu and ‘Eua.

The country could be without internet for up to two weeks with the undersea communications cables that connect Tonga to the rest of the world damaged.

Samiuela Fonua, the chairperson of the state-owned Tonga Cable Ltd, which owns and operates the cables, told the Guardian that it’s taking time to repair due to the risks that a subsequent volcanic eruption could endanger a repair ship.

“The main concern now is with the volcanic activities because our cables are pretty much on the same zone,” he said.

Modelling suggests there will be ongoing eruptions over the next few weeks, with and ongoing tsunami risk to Tonga and its neighbors.

Photos leaked online from a New Zealand Defense Force reconnaissance flight to Tonga show extensive damage to much of the country, with photos of Mango Island tagged as having “catastrophic damage.”

Tonga’s deputy head of mission in Australia, Curtis Tu’ihalangingie said the images were “alarming.”

“People panic, people run and get injuries. Possibly there will be more deaths and we just pray that is not the case,” he told Reuters.

Tonga is made up of 169 islands, 36 of which are inhabited. It’s expected to take weeks to survey the scale of the damage.

Australia has so far committed A$1 million in funding for Tonga and has dispatched the HMAS Adelaide gunship, loaded with medical and engineering equipment, as well as personnel. Australian helicopters will use the vessel as a base to service populations on outer islands. Australian C130 Hercules aircraft will also leave for Tonga once the runway has been cleared. Further funding is expected once Australia receives detailed advice from the Tongan government.

New Zealand has also allocated NZ$1 million in funding and has said once the runway is clear it will dispatch its own C130 Hercules flight with humanitarian assistance.

“In the meantime, two Royal New Zealand Navy ships will depart New Zealand today. HMNZS Wellington will be carrying Hydrographic Survey and Diving Teams, as well as an SH-2G(I) Seasprite helicopter. HMNZS Aotearoa will carry bulk water supplies and humanitarian and disaster relief stores,” said Defense Minister Peeni Hernare

“Water is among the highest priorities for Tonga at this stage and HMNZS Aotearoa can carry 250,000 litres, and produce 70,000 litres per day through a desalination plant.”

Tonga is currently COVID-free and operates strict border controls to keep the virus out. Continuing to keep COVID-19 out while bringing aid in will present significant challenges for the country.

By Joshua Mcdonald for The Diplomat

5-6 minutes

Oceania | Society | Oceania

Tonga is made up of 169 islands, 36 of which are inhabited. It’s expected to take weeks to survey the scale of the damage.

In this photo provided by the New Zealand Defense Force, volcanic ash covers roof tops and vegetation in an area of Tonga, Monday, January 17, 2022.

Credit: CPL Vanessa Parker/NZDF via AP)

The government of Tonga issued its first statement since a violent volcanic eruption occurred Saturday that caused tsunami waves to wreak havoc across the country, leaving at least three people dead, towns destroyed, and the country without internet for several days.

“As a result of the eruption, a volcanic mushroom plume was released reaching the stratosphere and extending radially covering all Tonga Islands, generating tsunami waves rising up to 15 metres, hitting the west coasts of Tongatapu Islands, ‘Eva, and Ha’apai Islands,” the government said.

“To date, there are 3 confirmed fatalities including a British national; a 65-year-old female from Mango Island; and a 49-year-old male from Nomuka Island. There are also a number of injuries reported.”

The government said not a single house is left standing on Mango Island, only two houses remain on Fonoifua Island, and extensive damage has been caused to other islands. It added that evacuation efforts are underway across the country.

The volcanic ash that blanketed Tonga has severely affected water supplies and made any effort by Tonga’s neighbors to fly in support extremely dangerous.

“Challenges to sea and air transportation remain due to damage sustained by the wharves and the ash that is covering the runways,” the government said. “Domestic and international flights have been deferred until further notice as the airports undergo clean-up.”

The government added that communication is still a key issue, with internet still down while domestic phone calls can only operate within the areas of Tongatapu and ‘Eua.

The country could be without internet for up to two weeks with the undersea communications cables that connect Tonga to the rest of the world damaged.

Samiuela Fonua, the chairperson of the state-owned Tonga Cable Ltd, which owns and operates the cables, told the Guardian that it’s taking time to repair due to the risks that a subsequent volcanic eruption could endanger a repair ship.

“The main concern now is with the volcanic activities because our cables are pretty much on the same zone,” he said.

Modelling suggests there will be ongoing eruptions over the next few weeks, with and ongoing tsunami risk to Tonga and its neighbors.

Photos leaked online from a New Zealand Defense Force reconnaissance flight to Tonga show extensive damage to much of the country, with photos of Mango Island tagged as having “catastrophic damage.”

Tonga’s deputy head of mission in Australia, Curtis Tu’ihalangingie said the images were “alarming.”

“People panic, people run and get injuries. Possibly there will be more deaths and we just pray that is not the case,” he told Reuters.

Tonga is made up of 169 islands, 36 of which are inhabited. It’s expected to take weeks to survey the scale of the damage.

Australia has so far committed A$1 million in funding for Tonga and has dispatched the HMAS Adelaide gunship, loaded with medical and engineering equipment, as well as personnel. Australian helicopters will use the vessel as a base to service populations on outer islands. Australian C130 Hercules aircraft will also leave for Tonga once the runway has been cleared. Further funding is expected once Australia receives detailed advice from the Tongan government.

New Zealand has also allocated NZ$1 million in funding and has said once the runway is clear it will dispatch its own C130 Hercules flight with humanitarian assistance.

“In the meantime, two Royal New Zealand Navy ships will depart New Zealand today. HMNZS Wellington will be carrying Hydrographic Survey and Diving Teams, as well as an SH-2G(I) Seasprite helicopter. HMNZS Aotearoa will carry bulk water supplies and humanitarian and disaster relief stores,” said Defense Minister Peeni Hernare

“Water is among the highest priorities for Tonga at this stage and HMNZS Aotearoa can carry 250,000 litres, and produce 70,000 litres per day through a desalination plant.”

Tonga is currently COVID-free and operates strict border controls to keep the virus out. Continuing to keep COVID-19 out while bringing aid in will present significant challenges for the country.

Volcanic Eruption Devastates Tonga

Tonga is made up of 169 islands, 36 of which are inhabited. It’s expected to take weeks to survey the scale of the damage.

thediplomat.com

jward

passin' thru

Simon Proud

@simon_sat

Based on analysis of data from global weather satellites, our preliminary data for the #Tonga volcanic cloud suggests that it reached an altitude of 39km (128,000ft). We'll refine the accuracy of that in the coming days, but if correct that's the highest cloud we've ever seen.

I should add: These are unheard of altitudes and our usual methods do not work as well up there. Even if this gets corrected downwards it will still be extraordinarily high, I can't see it being below 30km in any case.

John Peters

@UpdraftwMax

Replying to @simon_sat

This fits with the relatively basic parcel theory calculations which give a 40-43 km plume height (for the overshoot). Incredible. Probably the highest convective "cloud" on earth since Pinatubo.

Andrew Tupper

@andrewcraigtupp

Jan 18

Replying to @simon_sat

Except for Pinatubo? I’m assuming the 40 km still stands, although instruments were not so good then.

@nathanaelmelia

Replying to @simon_sat

I've seen analysis that the vertical velocity of the initial plume was more than 300m/s I.e. parcel. Traditional buoyant parcel methods are going to be an underestimate I imagine, considering the plume was in the stratosphere so fast.

xflo:w

@xflow

Replying to @simon_sat

That's the thing, even if it gets corrected down by 10 or 15% then it's still way above 30. And the column starts at zero metres. Hunga-Tonga is at sea level, and not 3.7km high like f.e. Semeru volcano. That's a tremendous eruption!

vijay banga

@lekh27

Jan 18

Replying to @simon_sat @tanyaofmars @LadyVelvet_HFQ

From 17kms to 20kms to #Tonga volcanic cloud suggests that it reached an altitude of 39km ,most horrifying. Can global pollution conferences be of help. Ash will spread over 100sof miles,after effects last weeks and months

ben clark

@benclark12

Replying to @simon_sat

Thanks @simon_sat What does this bode for particulate matter reflecting sunligh away from earth and providing some temporary cooling effect?

@nathanaelmelia

Replying to @benclark12 and@simon_sat

Not enough SO2 for that.

jward

passin' thru

nationalgeographic.com

The volcanic explosion in Tonga destroyed an island—and created many mysteries

Maya Wei-Haas

For many years, the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai volcano poked above the waves as a pair of narrow rocky isles, one named Hunga Tong and the other Hunga Ha'apai. An eruption in 2014 built up a third island that later connected the trio into one landmass. And when the volcano awoke in December, the uninhabited island at the peak's tip slowly grew as bits of volcanic rock and ash built up new land.

Then came the catastrophic eruption on January 15. As seen in satellite images, only two tiny outcrops of rock now betray the beast lurking beneath the waves. But whether it happens in weeks or years, the volcano will rise again.

This cycle of destruction and rebirth is the lifeblood of volcanoes like Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai, which is just one of many that dot the Kingdom of Tonga. Still, the tremendous energy of this latest explosion, which NASA estimated to be equivalent to five to six million tons of TNT, is unlike any seen in recent decades. The eruption sent a tsunami racing across the Pacific Ocean. It unleashed a sonic boom that zipped around the world twice. It sent a plume of ash and gas shooting into the stratosphere some 19 miles high, with some parts reaching as far as 34 miles up. And perhaps most remarkable, all these effects came from only an hour or so of volcanic fury.

"Everything so far about this eruption is off-the-scale weird," says Janine Krippner, a volcanologist with Smithsonian's Global Volcanism Program.

Scientists are now racing to work out the cause behind this week’s intense outburst and the surprisingly widespread tsunamis that followed. Some clues to what set the stage for such a powerful explosion may come from the chemistry of rocks that cooled from lava in past eruptions. In a new study published in the journal Lithos, scientists found key differences between the erupted material of small and large blasts—and now they are curious what the chemistry of this latest event might reveal.

Understanding the spark that ignited Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai’s recent explosive event could help reduce future risks. For now, however, the biggest concern is for the people of Tonga, and whether there could be more volcanic outbursts on the horizon. Almost all of the volcano is now beneath the ocean surface, hidden from satellite view, and there's no equipment on the ground to help track subterranean shifts of molten rock.

"If we can't detect what is happening in the magma system, we have no idea what might happen next," Krippner says.

An underwater giant

While Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai has erupted many times in the past, scientists only recently realized how large these eruptions could be. Mostly submerged underwater, the volcano is not easy to study.

"No one had actually done any work on the rocks," says Simon Barker, a volcanologist at Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand and an author of the new Lithos study documenting the volcano's history.

Barker and his colleagues chartered a boat in 2015 to camp for several nights on the volcanic island’s rubbly landscape. As they surveyed the region and collected samples of rock, the team spotted small cones from recent eruptions dotting the seafloor around the primary peak. They also discovered thick layers of fragmented lava rocks and ash, known as pyroclastic flows, from two monstrous eruptions that they later dated to around 900 and 1,800 years old.

"We saw there was a lot more complexity to the history of the volcano," Barker says.

The chemistry of erupted material might help untangle what made this eruption so powerful, explains Marco Brenna, a volcanologist at the University of Otago in New Zealand and an author of the new Lithos study.

As a magma system cools, crystals of different minerals form at different times, which changes the chemistry of the dwindling molten rock. The crystals preserve these changes as they grow, a little like tree rings.

Brenna and his colleagues analyzed the rings of crystals in the rocks that erupted during the two large blasts 900 and 1,800 years ago. Their work suggests that before the volcano unleashed these eruptions, fresh magma was rapidly injected into the chamber—a commonly proposed trigger for many volcanic eruptions. But the rocks from more moderate explosions in 2008 and 2015 lacked these rings, pointing to a constant but slow influx of magma, Brenna says.

Scientists are now hoping to study the chemistry of the freshly erupted rock to see what it can tell us about this latest event. "It'll be interesting to see what the crystals are recording," Brenna says.

While these subterranean processes may be driving part of the explosivity, water also likely had a hand in this weekend's blasts, says Geoff Kilgour, a volcanologist with New Zealand's GNS Science who was not part of the study team. Water can supercharge the power of a volcanic explosion, but it remains unclear exactly how it would have sparked the astounding boom from Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai.

Perhaps, Kilgour suggests, the recent explosion had just the right mix of magma and water; an excess of either one would have generated a more moderate blast. "It may be that we've gotten to this Goldilocks zone," he says.

Airblast tsunami?

This latest eruption is layering on even more intrigue because its mighty boom, while energetic, ejected surprisingly little material. Ash from the volcano's past large eruptions can be found on the nearby island of Tongatapu, and that layer is 10 times thicker than the new layer deposited there by the recent event, Barker says.

Some scientists now speculate that the enormous, short-lived burst of energy may have helped stir up the unusually large tsunami waves that followed the eruption.

Tsunamis usually radiate from a sudden underwater shift, like a submarine landslide down a volcano's flanks or rapid movement of the land in an earthquake. Yet after Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai erupted, waves appeared in some places, such as the Caribbean, far earlier than would be expected of a classic tsunami.

The later tsunami waves that crashed on distant shores were also strange. The farther from the trigger a tsunami travels, the more its waves should diminish. While the waves that hit the islands in the Kingdom of Tonga were damaging, they weren't high enough to account for the surprisingly large waves across the ocean.

"It basically had a very low decay of tsunami size all around the Pacific, which is really, really unusual," Kilgour says. The shockwave that traveled through the air could have coupled with the sea surface, driving the expansive tsunamis. Just such a process was proposed for the 1883 explosion of Krakatoa, one of the most powerful and deadly volcanic eruptions in recorded history.

Modeling the spread and timing of the waves along with mapping changes to the volcano could help explain what drove the large tsunami. Still, Krippner says, the confusing mix of events "is going to change the way we look at this style of eruption—and that doesn't happen that often."

Trying to monitor a hidden giant

The recent event and all its oddities highlight how little is known about submarine volcanoes, says Jackie Caplan-Auerbach, a seismologist with Western Washington University. Many of these submerged giants linger in the deep ocean, and their blasts usually aren't deadly. Yet this weekend's explosion is a stark reminder of the risks of volcanoes lingering just beneath the waves.

For now, Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai seems to have fallen silent. The locals are helping each other pick through the damage and clean up the streets. While communications remain largely severed, information about the current situation is finally starting to trickle out. Three deaths have been confirmed among Tonga's residents, with two additional deaths in Peru from the tsunami.

Damage on some of the islands is severe. The homes of all 36 residents of Mango Island have been destroyed. Just two houses still stand on Fonoifua Island, and extensive damage stretches across Nomuka Island, which has a population of 239. Damage to the largest and most populous island, Tongatapu, where about 75,000 people live, was mostly focused on the western side. The Tonga Red Cross estimates a total of 1,200 "affected households."

Ash has contaminated the islands' stores of drinking water and delayed planes from landing with additional supplies. The New Zealand navy has deployed two supply ships that are scheduled to arrive on January 21.

And there's still a risk that the volcano could have more explosive blasts in store. The Tonga Geological Services relies on visual and satellite observations to track the activity of the many volcanoes across the region. But with Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai’s volcanic tip now beneath the surface, scientists have lost sight of any signs that might help understand the volcano's activity. The potential for additional activity also prevents scientists from flying nearby for a closer look.

Even when the volcano isn't actively erupting, monitoring largely submarine volcanoes is a complex task. GPS—which is frequently used to track shifts in the surface as magma moves underground—doesn't work on the seafloor. And obtaining real-time data from seismometers on the ocean floor is technologically difficult and expensive. Caplan-Auerbach says she often likens working in the oceans to doing seismology on another planet.

Instruments known as hydrophones can listen to the grumbles of submarine volcanoes as the sound travels across vast tracts of the ocean. But these are not easy to deploy in emergency situations and require connection to underwater cables for real-time data.

The situation in Tonga highlights the need for better international efforts to fund volcano monitoring around the world, Krippner says. She and other volcanologists have all stressed how well the Tonga Geological Services is handling a near-impossible task. "They don't have a huge amount of money. They don't have a huge amount of staff," Kilgour says. "But they're asked to do a huge amount."

In the days leading up to the January 15 blast, based on visual and satellite information alone, the agency persistently warned of future eruptions and a potential tsunami, instructing locals to stay away from the beaches. "Because of that, I think they saved probably thousands of lives," Barker says.

"We often learn from these really dreadful times," Caplan-Aurbach adds. Perhaps by closely studying the aftermath of this volcanic explosion, "we'll have a better sense for what's coming."

www.nationalgeographic.com

www.nationalgeographic.com

The volcanic explosion in Tonga destroyed an island—and created many mysteries

Maya Wei-Haas

For many years, the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai volcano poked above the waves as a pair of narrow rocky isles, one named Hunga Tong and the other Hunga Ha'apai. An eruption in 2014 built up a third island that later connected the trio into one landmass. And when the volcano awoke in December, the uninhabited island at the peak's tip slowly grew as bits of volcanic rock and ash built up new land.

Then came the catastrophic eruption on January 15. As seen in satellite images, only two tiny outcrops of rock now betray the beast lurking beneath the waves. But whether it happens in weeks or years, the volcano will rise again.

This cycle of destruction and rebirth is the lifeblood of volcanoes like Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai, which is just one of many that dot the Kingdom of Tonga. Still, the tremendous energy of this latest explosion, which NASA estimated to be equivalent to five to six million tons of TNT, is unlike any seen in recent decades. The eruption sent a tsunami racing across the Pacific Ocean. It unleashed a sonic boom that zipped around the world twice. It sent a plume of ash and gas shooting into the stratosphere some 19 miles high, with some parts reaching as far as 34 miles up. And perhaps most remarkable, all these effects came from only an hour or so of volcanic fury.

"Everything so far about this eruption is off-the-scale weird," says Janine Krippner, a volcanologist with Smithsonian's Global Volcanism Program.

Scientists are now racing to work out the cause behind this week’s intense outburst and the surprisingly widespread tsunamis that followed. Some clues to what set the stage for such a powerful explosion may come from the chemistry of rocks that cooled from lava in past eruptions. In a new study published in the journal Lithos, scientists found key differences between the erupted material of small and large blasts—and now they are curious what the chemistry of this latest event might reveal.

Understanding the spark that ignited Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai’s recent explosive event could help reduce future risks. For now, however, the biggest concern is for the people of Tonga, and whether there could be more volcanic outbursts on the horizon. Almost all of the volcano is now beneath the ocean surface, hidden from satellite view, and there's no equipment on the ground to help track subterranean shifts of molten rock.

"If we can't detect what is happening in the magma system, we have no idea what might happen next," Krippner says.

An underwater giant

While Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai has erupted many times in the past, scientists only recently realized how large these eruptions could be. Mostly submerged underwater, the volcano is not easy to study.

"No one had actually done any work on the rocks," says Simon Barker, a volcanologist at Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand and an author of the new Lithos study documenting the volcano's history.

Barker and his colleagues chartered a boat in 2015 to camp for several nights on the volcanic island’s rubbly landscape. As they surveyed the region and collected samples of rock, the team spotted small cones from recent eruptions dotting the seafloor around the primary peak. They also discovered thick layers of fragmented lava rocks and ash, known as pyroclastic flows, from two monstrous eruptions that they later dated to around 900 and 1,800 years old.

"We saw there was a lot more complexity to the history of the volcano," Barker says.

The chemistry of erupted material might help untangle what made this eruption so powerful, explains Marco Brenna, a volcanologist at the University of Otago in New Zealand and an author of the new Lithos study.

As a magma system cools, crystals of different minerals form at different times, which changes the chemistry of the dwindling molten rock. The crystals preserve these changes as they grow, a little like tree rings.

Brenna and his colleagues analyzed the rings of crystals in the rocks that erupted during the two large blasts 900 and 1,800 years ago. Their work suggests that before the volcano unleashed these eruptions, fresh magma was rapidly injected into the chamber—a commonly proposed trigger for many volcanic eruptions. But the rocks from more moderate explosions in 2008 and 2015 lacked these rings, pointing to a constant but slow influx of magma, Brenna says.

Scientists are now hoping to study the chemistry of the freshly erupted rock to see what it can tell us about this latest event. "It'll be interesting to see what the crystals are recording," Brenna says.

While these subterranean processes may be driving part of the explosivity, water also likely had a hand in this weekend's blasts, says Geoff Kilgour, a volcanologist with New Zealand's GNS Science who was not part of the study team. Water can supercharge the power of a volcanic explosion, but it remains unclear exactly how it would have sparked the astounding boom from Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai.

Perhaps, Kilgour suggests, the recent explosion had just the right mix of magma and water; an excess of either one would have generated a more moderate blast. "It may be that we've gotten to this Goldilocks zone," he says.

Airblast tsunami?

This latest eruption is layering on even more intrigue because its mighty boom, while energetic, ejected surprisingly little material. Ash from the volcano's past large eruptions can be found on the nearby island of Tongatapu, and that layer is 10 times thicker than the new layer deposited there by the recent event, Barker says.

Some scientists now speculate that the enormous, short-lived burst of energy may have helped stir up the unusually large tsunami waves that followed the eruption.

Tsunamis usually radiate from a sudden underwater shift, like a submarine landslide down a volcano's flanks or rapid movement of the land in an earthquake. Yet after Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai erupted, waves appeared in some places, such as the Caribbean, far earlier than would be expected of a classic tsunami.

The later tsunami waves that crashed on distant shores were also strange. The farther from the trigger a tsunami travels, the more its waves should diminish. While the waves that hit the islands in the Kingdom of Tonga were damaging, they weren't high enough to account for the surprisingly large waves across the ocean.

"It basically had a very low decay of tsunami size all around the Pacific, which is really, really unusual," Kilgour says. The shockwave that traveled through the air could have coupled with the sea surface, driving the expansive tsunamis. Just such a process was proposed for the 1883 explosion of Krakatoa, one of the most powerful and deadly volcanic eruptions in recorded history.

Modeling the spread and timing of the waves along with mapping changes to the volcano could help explain what drove the large tsunami. Still, Krippner says, the confusing mix of events "is going to change the way we look at this style of eruption—and that doesn't happen that often."

Trying to monitor a hidden giant

The recent event and all its oddities highlight how little is known about submarine volcanoes, says Jackie Caplan-Auerbach, a seismologist with Western Washington University. Many of these submerged giants linger in the deep ocean, and their blasts usually aren't deadly. Yet this weekend's explosion is a stark reminder of the risks of volcanoes lingering just beneath the waves.

For now, Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai seems to have fallen silent. The locals are helping each other pick through the damage and clean up the streets. While communications remain largely severed, information about the current situation is finally starting to trickle out. Three deaths have been confirmed among Tonga's residents, with two additional deaths in Peru from the tsunami.

Damage on some of the islands is severe. The homes of all 36 residents of Mango Island have been destroyed. Just two houses still stand on Fonoifua Island, and extensive damage stretches across Nomuka Island, which has a population of 239. Damage to the largest and most populous island, Tongatapu, where about 75,000 people live, was mostly focused on the western side. The Tonga Red Cross estimates a total of 1,200 "affected households."

Ash has contaminated the islands' stores of drinking water and delayed planes from landing with additional supplies. The New Zealand navy has deployed two supply ships that are scheduled to arrive on January 21.

And there's still a risk that the volcano could have more explosive blasts in store. The Tonga Geological Services relies on visual and satellite observations to track the activity of the many volcanoes across the region. But with Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai’s volcanic tip now beneath the surface, scientists have lost sight of any signs that might help understand the volcano's activity. The potential for additional activity also prevents scientists from flying nearby for a closer look.

Even when the volcano isn't actively erupting, monitoring largely submarine volcanoes is a complex task. GPS—which is frequently used to track shifts in the surface as magma moves underground—doesn't work on the seafloor. And obtaining real-time data from seismometers on the ocean floor is technologically difficult and expensive. Caplan-Auerbach says she often likens working in the oceans to doing seismology on another planet.

Instruments known as hydrophones can listen to the grumbles of submarine volcanoes as the sound travels across vast tracts of the ocean. But these are not easy to deploy in emergency situations and require connection to underwater cables for real-time data.

The situation in Tonga highlights the need for better international efforts to fund volcano monitoring around the world, Krippner says. She and other volcanologists have all stressed how well the Tonga Geological Services is handling a near-impossible task. "They don't have a huge amount of money. They don't have a huge amount of staff," Kilgour says. "But they're asked to do a huge amount."

In the days leading up to the January 15 blast, based on visual and satellite information alone, the agency persistently warned of future eruptions and a potential tsunami, instructing locals to stay away from the beaches. "Because of that, I think they saved probably thousands of lives," Barker says.

"We often learn from these really dreadful times," Caplan-Aurbach adds. Perhaps by closely studying the aftermath of this volcanic explosion, "we'll have a better sense for what's coming."

The volcanic explosion in Tonga destroyed an island—and created many mysteries

"Everything so far about this eruption is off-the-scale weird," from its deafening blast to its Pacific-wide tsunami.

packyderms_wife

Neither here nor there.

They just said on the local news that the shockwave was felt as far away as Switzerland and Antarctica. No link, this was on Ch. 13 Des Moines, IA, NBC channel.

jed turtle

a brother in the Lord

I personally am waiting for some scientist to definitely rule out that it was a nuclear weapon as some have maintained. I want to hear that there is NO sign of radiation, because everything else suggests an EXTRAORDINARY event...

Lone_Hawk

Resident Spook

I personally am waiting for some scientist to definitely rule out that it was a nuclear weapon as some have maintained. I want to hear that there is NO sign of radiation, because everything else suggests an EXTRAORDINARY event...

If it was a nuke, the whole world would know it. Nukes have a very distinctive reading on seismographic equipment that can't be hidden.

packyderms_wife

Neither here nor there.

I personally am waiting for some scientist to definitely rule out that it was a nuclear weapon as some have maintained. I want to hear that there is NO sign of radiation, because everything else suggests an EXTRAORDINARY event...

It was an extraordinary event, just like Tambora was.

Aftermath of the Biggest Eruption Ever Seen from Space - Tonga

RT 10:10

Jan 22, 2022

View: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sZZVVwqZ0rs&ab_channel=Astrum

RT 10:10

Jan 22, 2022

The aftermath of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai Jan 15 2022 eruption. Claim your SPECIAL OFFER for MagellanTV here: https://try.magellantv.com/astrum. Start your free trial TODAY so you can watch "Guatemala: Volcanoes on Mayan Territory", and the rest of MagellanTV’s science collection: https://www.magellantv.com/video/guat...

jward

passin' thru

Eyewitness: Volcano, tsunami devastate Tonga, help urgently needed

Cleo Paskal

The night before the major volcanic eruption. Photo: Tevita Motulalo

World Exclusive: ‘One could see the huge smoke column from the volcano shoot straight up from the horizon into the sky, until you couldn’t see it anymore. It’s almost as if it was erupting into space itself.’

Alexandria, Virginia: In this edition of Indo-Pacific: Behind the Headlines we speak with Mr Tevita Motulalo, a veteran journalist, security analyst and strategic communications consultant from the Kingdom of Tonga.

Communications with Tonga have been largely cut off since a major volcanic eruption on 15 January broke the country’s underwater fiber optic cable and triggered a tsunami that was felt as far away as Japan and California. Mr Motulalo, who is in Tonga, answered questions by text during a brief window of stable communications.

Q: Can you describe what happened?

A: It started a few weeks earlier. The volcano had been spewing out ash and smoke for weeks, but because the usual wind direction is east-south-easterly, it carried the effluents northeast towards Fiji.

When there were signs of the volcano reigniting and showing signs of erupting. The National Meteorological Office did the best they could. But there’s relatively little public or political attention to key vital and security issues—including and especially non-traditional security threats like environmental disasters.

The Friday before the eruption, after more violent eruption were recorded and sulfuric fumes reached entirety of the main island Tongatapu, a tsunami warning was issued. The wind turned in the opposite direction because of a [weather] depression ongoing just above north Island of New Zealand and that whipped the huge ash column towards Tongatapu, where the majority of the population lives.

Evacuations were held, but it was all too novel. By the end of Friday all we saw were dramatic tidal shifts in the afternoon. And the tsunami warning issued earlier was cancelled.

Tevita Motulalo

Tevita Motulalo

On Saturday, at around 5pm in the afternoon, the first of the now very loud explosions were heard. It’s like the heavens were about to rip into pieces. There were very loud cracks not experienced in our lived experiences since antiquity—and the elders have lived through a few eruptions and national evacuations of their own. Glass and curtains were blown off the windows in places.

Shortly afterwards, the first of the waves arrived. It has to be said, none of the early warning systems worked. What worked was the loud explosions from the volcano. We were joking to each other that it was loud enough for even the deaf to hear it and the blind to see it.

Traffic started to jam on the main vein leading traffic out of the city towards the more elevated portions of the island. When the waves arrived, most of the people—having been aware of the tsunami warning issued a day earlier—had moved inland.

The warnings systems failed on the spot. The national meteorological office went offline with the previous day’s tsunami cancellation still up. No updates. And at the moment of the explosion, Cabinet was on the outskirts of the island for some occasion. They had to fight through the outpouring traffic jam to get back to stations.

One could see the huge smoke column from the volcano shoot straight up from the horizon into the sky, until you couldn’t see it anymore. It’s almost as if it was erupting into space itself. Then the huge vague shadow of dust mushroomed behind the heavens and covered half the sky.

An hour or so after the explosions, small volcanic pumice and pebbles of half a centimeter made landfall. Shortly afterwards, the ash arrived. It also arrived with a strong gust that blew the debris everywhere. This forced cars full of women and children to close their windows, which made the insides of cars like small ovens.

When the waves hit, the western strip of the island—about two miles wide—was overrun by the waves. Waves broke at one beach, ran through overland, and flowed out on the other side.

Immediately, internet and cellular communications were in and out. A few hours later, the power had to be cut as the piling ash was causing transformers to short. And so we were in a darkness with an orange-reddish hue, at the hilltops and evacuation centers inland.

It was almost Biblical: The strong gusts, the stinging falling pebbles and the blinding ash were accompanied by the wailing of women and the screeching cries of babies and infants—and the whispers among fathers and sons standing guard outside their vehicles that the waves have wiped out part of the island and are now heading their way. From fear, from the hot weather, lack of water, and the entire situation—if there was a picture of Sheol where there’s crying and gnashing of teeth that would probably be the closest I’d get.

Evacuees were stranded on the hills thirsty, right next to the national water company’s reservoirs. I managed to get through the line to a cousin at the company to ask for the facility operator to open up the taps.

But in a couple more hours the ash cloud waned to just sprinkles, and after a few hours it was clear the waters have retreated and the waves receded.

Q: What’s the situation like now?

A: We are living the experience of the shockwave of several Hiroshima bombs going off in the neighborhood. There have been three deaths. Most of the waterfront [in the capital, Nuku’alofa] is gone. The Hihifo strip was overrun from coast to coast. The port in the capital, the fuel depot and the fuel terminal lines are out. But people are amazing.

Our greatest challenge at moment is energy. The offloading lines from tankers were damaged. I’m not sure how much we have in stock. Tongatapu [the capital] has some leeway in whatever stocks of fuel are available. But it won’t last. They said there’s enough but I have a feeling they’re just saying that to quell fears of shortage. But if we are out of fuel, then water and power are out. All communications are out. Relief operations are out.

Food supply on the main island is ok. The outer islands may need food, and they were hit with the waves so their crops and soils are saltwater damaged. Damage surveillance is ongoing in Ha’apai [one of the outer island groups].

By the time the tsunami hit we were expecting a serious [atmospheric] depression potentially developing into a cyclone between us and Samoa. People are preparing for the next one.

Until yesterday [Saturday in Tonga] only local FM stations were still operational. Our communication infrastructure was almost completely totaled. There was no communication. All lines were down. Satellite phones are limited. We’re in the dark. So the situation in other parts of the country is not clear.

So far, there hasn’t been any adverse “issues” arising out of the recovery and there are no reports of extreme human suffering except loss of homes and entire villages dwellings, and the three fatalities. There were other injuries, but none reported on life support or life threatening apart, of course, from the systemic failures of institutions suffering from either incompetence, corruption, maladministration, or all simultaneously.

One good story? Atata island inhabitants were all wiped out into the ocean. All but one returned. A massive search operation went out. The missing guy managed to swim from Atata to the main island [around 13 kms, via two small islands], and reported himself found again at the central police station.

Q: How is the recovery going?

A: The recovery is handled by government to the best of its abilities. It’s a new government, just sworn in. Cabinet is still operating directly. But there is no “depth” in government planning. Everything is almost ad hoc. No contingency, no redundancy. And we’re in the middle of the cyclone season. We have full moons so there were King Tides last week. It was a perfect storm—we got away “easy” so far.

Communications infrastructure is laughable at moment in spite of the millions poured into it over the years. So super-redundant services like Starlink are absolutely relevant at this point. This applies to energy also in terms of decentralized virtual power plants and letting homes be net generators not just consumers.

The bureaucracy needs to upgrade its operational systems, and Parliament and Cabinet need to consider security (not securitization) properly and not relegate entirely to traditional military doctrine. Civil defense, which seems to work best thus far in mobilization against non-traditional security events, is something to consider.

Q: Are there any other issues developing that you are concerned about?

A: The retail industry, which feeds households with proteins, drinking water, and other household groceries, is majority controlled by Chinese investment. It has very often attempted price gouging in times of national shortage—and I’m not just talking about since the pandemic. There were a lot of instances where people turned up for water or food on the night of the tsunami and they shut their doors or credit to people in trouble. Which should be illegal.

Also in the event those shops get hit, they’ll be at the forefront of government assistance out of Tongan taxes. People might not too much mind them bribing officials to get into the country and make their fortunes out of Tongan poverty, but if they behave this way it’ll get really ugly. And the sentiment is starting to sour out of those reports.

Q: Anything you are watching in terms of foreign assistance?

A: We could really use something like a US Marines HA/DR logistics and training center in the region—maybe even Quad. Or during this crisis a visit from a Marine Expeditionary Unit or the sort of U.S. Navy deployment we used to see in the area in a time of crisis, like an LHD. In the meantime, China is about to offer huge assistance following the event.

Tevita Motulalo was the co-Founder of the Royal Oceania Institute, the Kingdom of Tonga’s independent think tank, and was formerly a Senior Researcher at Gateway House think tank, Mumbai. He was awarded his Masters from the Department of Geopolitics and International Relations, Manipal, India.

Cleo Paskal is The Sunday Guardian Special Correspondent and a Senior Fellow at the Foundation for Defense of democracies.

Cleo Paskal

- Published

- :

- January 23, 2022,

- 8:49 am

- |

- Updated

- :

- January 23, 2022,

- 8:56 AM

The night before the major volcanic eruption. Photo: Tevita Motulalo

World Exclusive: ‘One could see the huge smoke column from the volcano shoot straight up from the horizon into the sky, until you couldn’t see it anymore. It’s almost as if it was erupting into space itself.’

Alexandria, Virginia: In this edition of Indo-Pacific: Behind the Headlines we speak with Mr Tevita Motulalo, a veteran journalist, security analyst and strategic communications consultant from the Kingdom of Tonga.

Communications with Tonga have been largely cut off since a major volcanic eruption on 15 January broke the country’s underwater fiber optic cable and triggered a tsunami that was felt as far away as Japan and California. Mr Motulalo, who is in Tonga, answered questions by text during a brief window of stable communications.

Q: Can you describe what happened?

A: It started a few weeks earlier. The volcano had been spewing out ash and smoke for weeks, but because the usual wind direction is east-south-easterly, it carried the effluents northeast towards Fiji.

When there were signs of the volcano reigniting and showing signs of erupting. The National Meteorological Office did the best they could. But there’s relatively little public or political attention to key vital and security issues—including and especially non-traditional security threats like environmental disasters.

The Friday before the eruption, after more violent eruption were recorded and sulfuric fumes reached entirety of the main island Tongatapu, a tsunami warning was issued. The wind turned in the opposite direction because of a [weather] depression ongoing just above north Island of New Zealand and that whipped the huge ash column towards Tongatapu, where the majority of the population lives.

Evacuations were held, but it was all too novel. By the end of Friday all we saw were dramatic tidal shifts in the afternoon. And the tsunami warning issued earlier was cancelled.

On Saturday, at around 5pm in the afternoon, the first of the now very loud explosions were heard. It’s like the heavens were about to rip into pieces. There were very loud cracks not experienced in our lived experiences since antiquity—and the elders have lived through a few eruptions and national evacuations of their own. Glass and curtains were blown off the windows in places.

Shortly afterwards, the first of the waves arrived. It has to be said, none of the early warning systems worked. What worked was the loud explosions from the volcano. We were joking to each other that it was loud enough for even the deaf to hear it and the blind to see it.

Traffic started to jam on the main vein leading traffic out of the city towards the more elevated portions of the island. When the waves arrived, most of the people—having been aware of the tsunami warning issued a day earlier—had moved inland.

The warnings systems failed on the spot. The national meteorological office went offline with the previous day’s tsunami cancellation still up. No updates. And at the moment of the explosion, Cabinet was on the outskirts of the island for some occasion. They had to fight through the outpouring traffic jam to get back to stations.

One could see the huge smoke column from the volcano shoot straight up from the horizon into the sky, until you couldn’t see it anymore. It’s almost as if it was erupting into space itself. Then the huge vague shadow of dust mushroomed behind the heavens and covered half the sky.

An hour or so after the explosions, small volcanic pumice and pebbles of half a centimeter made landfall. Shortly afterwards, the ash arrived. It also arrived with a strong gust that blew the debris everywhere. This forced cars full of women and children to close their windows, which made the insides of cars like small ovens.

When the waves hit, the western strip of the island—about two miles wide—was overrun by the waves. Waves broke at one beach, ran through overland, and flowed out on the other side.

Immediately, internet and cellular communications were in and out. A few hours later, the power had to be cut as the piling ash was causing transformers to short. And so we were in a darkness with an orange-reddish hue, at the hilltops and evacuation centers inland.

It was almost Biblical: The strong gusts, the stinging falling pebbles and the blinding ash were accompanied by the wailing of women and the screeching cries of babies and infants—and the whispers among fathers and sons standing guard outside their vehicles that the waves have wiped out part of the island and are now heading their way. From fear, from the hot weather, lack of water, and the entire situation—if there was a picture of Sheol where there’s crying and gnashing of teeth that would probably be the closest I’d get.

Evacuees were stranded on the hills thirsty, right next to the national water company’s reservoirs. I managed to get through the line to a cousin at the company to ask for the facility operator to open up the taps.

But in a couple more hours the ash cloud waned to just sprinkles, and after a few hours it was clear the waters have retreated and the waves receded.

Q: What’s the situation like now?

A: We are living the experience of the shockwave of several Hiroshima bombs going off in the neighborhood. There have been three deaths. Most of the waterfront [in the capital, Nuku’alofa] is gone. The Hihifo strip was overrun from coast to coast. The port in the capital, the fuel depot and the fuel terminal lines are out. But people are amazing.

Our greatest challenge at moment is energy. The offloading lines from tankers were damaged. I’m not sure how much we have in stock. Tongatapu [the capital] has some leeway in whatever stocks of fuel are available. But it won’t last. They said there’s enough but I have a feeling they’re just saying that to quell fears of shortage. But if we are out of fuel, then water and power are out. All communications are out. Relief operations are out.

Food supply on the main island is ok. The outer islands may need food, and they were hit with the waves so their crops and soils are saltwater damaged. Damage surveillance is ongoing in Ha’apai [one of the outer island groups].

By the time the tsunami hit we were expecting a serious [atmospheric] depression potentially developing into a cyclone between us and Samoa. People are preparing for the next one.

Until yesterday [Saturday in Tonga] only local FM stations were still operational. Our communication infrastructure was almost completely totaled. There was no communication. All lines were down. Satellite phones are limited. We’re in the dark. So the situation in other parts of the country is not clear.

So far, there hasn’t been any adverse “issues” arising out of the recovery and there are no reports of extreme human suffering except loss of homes and entire villages dwellings, and the three fatalities. There were other injuries, but none reported on life support or life threatening apart, of course, from the systemic failures of institutions suffering from either incompetence, corruption, maladministration, or all simultaneously.

One good story? Atata island inhabitants were all wiped out into the ocean. All but one returned. A massive search operation went out. The missing guy managed to swim from Atata to the main island [around 13 kms, via two small islands], and reported himself found again at the central police station.

Q: How is the recovery going?

A: The recovery is handled by government to the best of its abilities. It’s a new government, just sworn in. Cabinet is still operating directly. But there is no “depth” in government planning. Everything is almost ad hoc. No contingency, no redundancy. And we’re in the middle of the cyclone season. We have full moons so there were King Tides last week. It was a perfect storm—we got away “easy” so far.

Communications infrastructure is laughable at moment in spite of the millions poured into it over the years. So super-redundant services like Starlink are absolutely relevant at this point. This applies to energy also in terms of decentralized virtual power plants and letting homes be net generators not just consumers.

The bureaucracy needs to upgrade its operational systems, and Parliament and Cabinet need to consider security (not securitization) properly and not relegate entirely to traditional military doctrine. Civil defense, which seems to work best thus far in mobilization against non-traditional security events, is something to consider.

Q: Are there any other issues developing that you are concerned about?

A: The retail industry, which feeds households with proteins, drinking water, and other household groceries, is majority controlled by Chinese investment. It has very often attempted price gouging in times of national shortage—and I’m not just talking about since the pandemic. There were a lot of instances where people turned up for water or food on the night of the tsunami and they shut their doors or credit to people in trouble. Which should be illegal.

Also in the event those shops get hit, they’ll be at the forefront of government assistance out of Tongan taxes. People might not too much mind them bribing officials to get into the country and make their fortunes out of Tongan poverty, but if they behave this way it’ll get really ugly. And the sentiment is starting to sour out of those reports.

Q: Anything you are watching in terms of foreign assistance?

A: We could really use something like a US Marines HA/DR logistics and training center in the region—maybe even Quad. Or during this crisis a visit from a Marine Expeditionary Unit or the sort of U.S. Navy deployment we used to see in the area in a time of crisis, like an LHD. In the meantime, China is about to offer huge assistance following the event.

Tevita Motulalo was the co-Founder of the Royal Oceania Institute, the Kingdom of Tonga’s independent think tank, and was formerly a Senior Researcher at Gateway House think tank, Mumbai. He was awarded his Masters from the Department of Geopolitics and International Relations, Manipal, India.

Cleo Paskal is The Sunday Guardian Special Correspondent and a Senior Fellow at the Foundation for Defense of democracies.

Eyewitness: Volcano, tsunami devastate Tonga, help urgently needed - The Sunday Guardian Live

World Exclusive: ‘One could see the huge smoke column from the volcano shoot straight up from the horizon into the sky, until you couldn’t see it anymore.

www.sundayguardianlive.com

jward

passin' thru

Elon Musk's Starlink Begins To "Reconnect Tonga To The World"

by Tyler Durden

Monday, Feb 07, 2022 - 05:26 PM

After a massive volcanic eruption that severed Tonga's internet connection to the world, a Fiji official tweeted Monday that a team of SpaceX engineers are in the process of establishing Starlink internet for the devastated island.

Last month, an undersea volcano about 40 miles north of Tonga's main island unleashed a massive shockwave that severed undersea internet communication lines with nearby Fiji. The volcanic eruption is believed to be the largest in three decades.

Fiji's Attorney-General Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum tweeted that a SpaceX team has arrived in Fiji and is working to "establish a Starlink Gateway station to reconnect Tonga to the world."

Tonga lies about 500 miles east of Fiji, and reconnecting the undersea communication cables could be costly and time-consuming. Erecting a Starlink gateway ground station in Fiji is quick and inexpensive compared to fixing undersea cables. A ground station links satellites in space with ground-based internet data centers. Here's an example of a ground station in Utah.

Elon Musk offered to restore Tonga's internet services on an emergency basis. However, he said the connection would be "hard" to establish because there weren't enough geostationary satellites that would connect the island.